Carving a Captain's Life—A Unique Family Record of a Maine Seaman Comes To Auction

It's a form of art that predates human civilization. The carving and crafting of images on bones and horns, teeth and tusks began before humanity possessed the skill of written language, and it extends even to our present day. This art goes by many names in many cultures, but the fundamental technique remains the same, requiring careful coordination of hand and eye, and a clear vision of the intended result. For sailors of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the practice of creating detailed carvings from the raw materials near at hand offered a welcome respite from the tiresome routine of life at sea. It was a hobby most often indulged in aboard whaling vessels, where teeth and fragments of whalebone offered a ready medium for elaborate decoration, and by the late 1820s, sailors called the resulting works "scrimshaw."

No one quite knows the origin of the word, and among enthusiasts today debates still rage over its proper definition. Some insist that true scrimshaw appears only on materials originating with whales. Others allow consideration of bones or teeth from other marine mammals. Others hew to a more flexible definition, and apply the term to any marine-themed engraving on any type of animal part. And still others consider scrimshaw any type of filled engraving regardless of thematic content, appearing on any type of polished bone, tooth, horn, or antler. While the argument will probably never be resolved to anyone's full satisfaction, there is ample surviving evidence that, historically, the type of carving associated with the word "scrimshaw" was not strictly confined to whale products, or even to whaling ships. Consider the example of one item appearing in our upcoming Winter Enchantment Auction — a two-foot-long powder horn depicting a lifetime of maritime adventure.

Outstanding Maritime Scrimshawn Powder Horn, on stand, by Louis Marc Francois Gauvin (born Saint-Servan, France, 1827; active Dalby and Paroo, Queensland, Australia), having full portrait of sailing ship "Ivanhoe" of Belfast, Maine, signed and dated 1881.

Upon examining this piece one immediately senses the weight of its history. It was carved by a sailor of French origin who spent a good part of his life in Australia. It depicts a proud sailing vessel of the late 19th Century, built and launched in Belfast, Maine, and it records the family record of a bold Maine captain whose career was marked by triumph and tragedy.

The artist was Louis Marc Francois Gauvin, born in St. Servan, France, in 1827, and captured early by the lure of the sea. He left home at a young age to serve aboard a French whaling vessel, where he learned to mend sails and fashion harpoons and lances. And it is very evident, from the considerable number of his pieces that survive, that he learned the art of scrimshaw. His voyages carried to the far corners of the world, but it was in Queensland, Australia that he decided, finally, to settle, to marry, and to raise a family. He plied the trade of sail-maker to apparently limited success, but he was far more successful as an artist. Lacking a ready source of whale products for carving, he instead turned to the inexhaustible supply of cattle horns available from the vast herds of central Queensland, and with a steady eye and a careful hand, worked them into objects of intricate beauty.

Having full portrait of sailing ship "Ivanhoe" of Belfast, Maine, signed and dated 1881.

Gauvin created these powder horns to order, intending them not for actual use in the field, but as ceremonial presentation pieces. He had clearly learned a great deal over the course of his travels, not simply about artistic technique, but the broader world around him. His work abounded in symbolism, mixing maritime motifs with Masonic imagery and occasional Latin mottoes. And unlike many scrimshanders of his generation, who did their work merely as a pastime, he was sufficiently conscious of his status as a professional artist to consistently sign his pieces -- as he did for the horn he created to commemorate the Belfast-built three-master named Ivanhoe.

Waldo County was a nexus of the New England shipbuilding industry during the middle of the nineteenth century, with shipyards dominating the economic and social lives of the neighboring communities of Searsport and Belfast. The yard founded in Belfast by Columbia Perkins Carter was one of the most notable The Carter firm spared no expense in the construction of its ships, building to a consistently high quality of materials and workmanship, and the Ivanhoe, constructed in 1864 at a cost of $164,000 was no exception. The 1610-ton vessel was fully equipped to carry a 3500-ton cargo. She was commissioned by Captain Edwin H. Herriman, one of Belfast's most noted seamen, and a favorite client of the Carter firm, and it was Herriman who commanded its initial voyages. He shifted in 1875 to an even more impressive vessel, the P. R. Hazeltine, largest ship ever constructed in Belfast. That vessel would prove Edward Herriman's ruin, foundering off the coast of Cape Horn, Chile in 1877. But the Ivanhoe continued in service under a new captain, Edwin's brother, Captain Albert H. Herriman.

Under A. H. Herriman's command, the Ivanhoe's voyages spanned the globe. It carried Maine lumber to Merseyside, England, and to Cardiff, Wales. It traversed South America to bring Eastern goods to waiting Californians. And from the burgeoning port of San Francisco it carried the flag of American commerce to far-flung Australia.

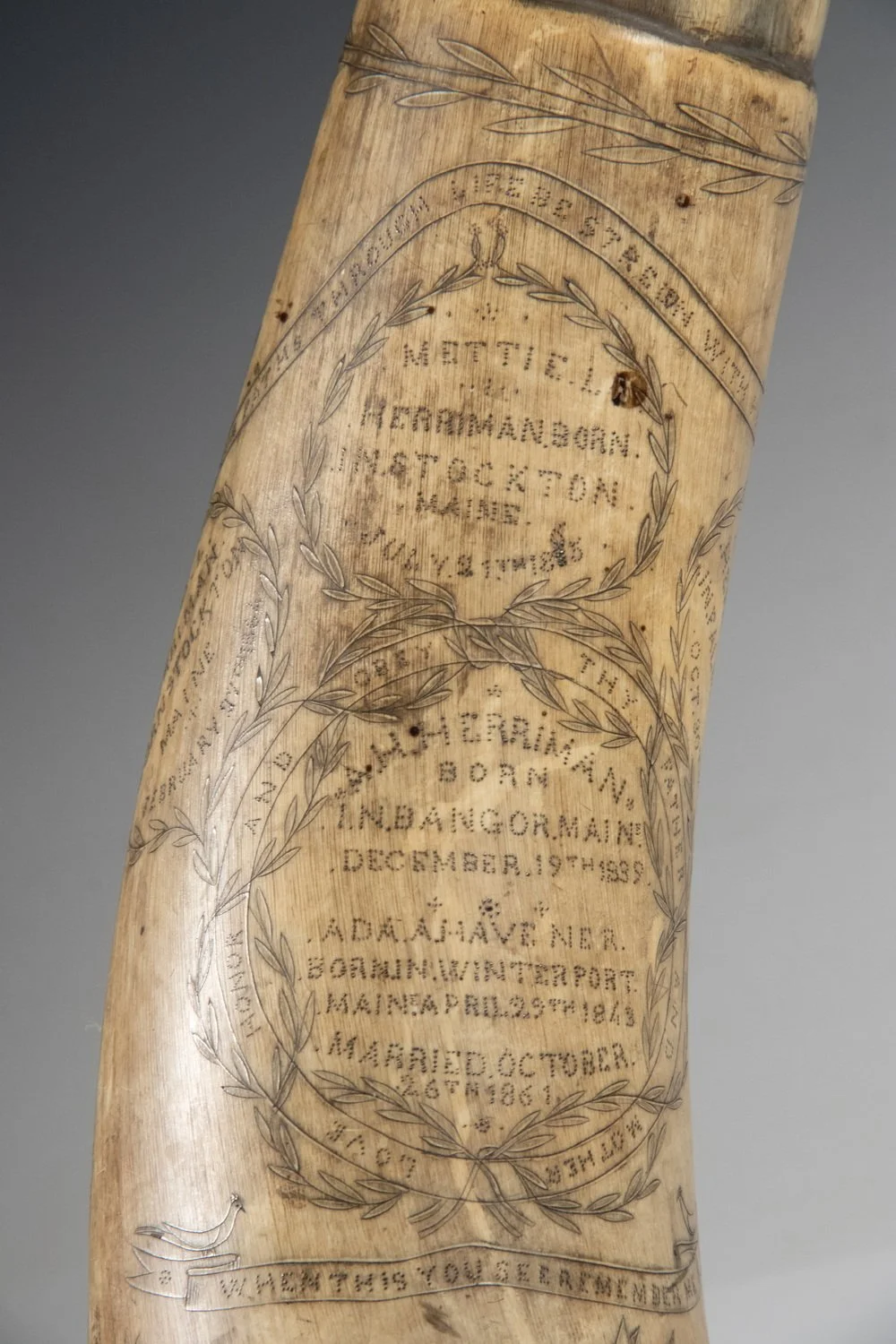

Detail of an exceptional Maritime Scrimshaw Powder Horn by Louis Marc Francois Gauvin, shown on stand and featured in our forthcoming Winter Enchantment Auction.

The cargoes it carried on these voyages weren't limited to merchandise. The ship also carried immigrants by the hundreds, leaving America for a new life Down Under, many of them Europeans utilizing the United States as a way stop on their way to join relatives who had already made the lengthy journey. But others were American citizens whose California gold-rush ambitions had long since played out, and were attracted by promises of future prosperity outlined in advertisements circulated by commercial agents of the Government of New South Wales. On one such voyage, one hundred and seventy-three men, women, and children sailed aboard the Ivanhoe, "a well respected lot of people," as one newspaper account described them, while speaking highly of Captain Herriman himself for his consideration of his passengers on his trip.

It was on one of these voyages that Captain Herriman and the Ivanhoe intersected with scrimshander Louis Gauvin, leading to the creation of another ceremonial powder horn in the Captain's honor. Whether Gauvin, by this time a married man with a family in Queensland, actually sailed aboard the Ivanhoe as a member of its crew, or if he merely visited the ship to create his artwork is uncertain. What is certain, however, is that he spent sufficient time with Albert Herriman to obtain sufficient personal information to inscribe the horn. It was common for many merchant captains of the late nineteenth century to bring along wives and children on their voyages, which may explain the pennants Gauvin depicts on his image of the Ivanhoe, carrying the initials of Albert F. Herriman and Ada Havener Herriman. But whether Gauvin met Mrs. Herriman and the children in person or not, his inscriptions reveal the Captain's deep affection for his family. The designs used by Gauvin in creating his Ivanhoe piece are consistent with the technique and symbolism he favored in carving many other, similar horns, a number of which exist in Australian collections. Few, however, seem to have found their way to the United States as this one did.

Albert Herriman captained the Ivanhoe until its sale in 1884 to a San Francisco coal concern. He remained in that city himself, going into partnership with a fellow Mainer, Warren F. Mills of Thomaston to establish a stevedoring agency, arranging the loading of cargoes aboard vessels bound for Pacific ports, and was eventually a key figure in the formation of a stevedoring trust seeking to control the trade for all ship-loading firms working out of San Francisco. That venture collapsed into a stew of infighting among the partners. Then, in 1901, while visiting Nome, Alaska, Ada Herriman died. Albert Herriman continued on in San Francisco, long enough to survive the Earthquake of 1906. Finally, alone and troubled by the aches and pains of advancing age, he returned to the East, and took up residence in an "Old Sailor's Home" called Snug Harbor, on Staten Island, New York. There he remained, a cordial man full of colorful stories, until his death in April 1917.

The family record of Captain Albert H. Herriman (born Dec. 19, 1839 in Bangor; married Ada H. Havener of Winterport, Maine (born Apr. 29, 1843), on Oct. 26, 1861. Three children are named.

The Ivanhoe's first master, sadly, came to a more tragic end. Captain Edwin H. Herriman never recovered from the shock and trauma of the loss of the Hazeltine. He made multiple futile efforts to locate the wreck and salvage the lost cargo, until broken in mind and body by the guilt he felt over the loss of the ship, he succumbed to what the newspapers of the day euphemized as "a mental aberration," and lived out the remainder of his days a patient in an Augusta mental institution. He died there in 1893. His Belfast home remains today on Congress Street, well known, with typical Maine bluntness, as "The Mad Captain's House."

The fate of Louis Marc Francois Gauvin is unknown. He vanishes from the historical record after the 1880s, though his widow Harriet died in Australia in 1916. He left behind a substantial legacy of unique artwork. A number of his pieces are proudly displayed by the Australia National Martime Museum.

As for the Ivanhoe itself, it carried cargo for the Black Diamond Coal Company until 1894. That September, the ship sailed under the command of Captain Edward D. Griffin from Seattle, Washington carrying a load of coal back to San Francisco, along with five passengers, among them a member of the Washington State House of Representatives, former minister to Bolivia, and part owner of Seattle's leading newspaper. As the vessel made its way southward, it sailed directly into a violent gale. The ship was never seen intact again, but wreckage attributed to the Ivanhoe washed up on northwestern shores for weeks after, until finally, newspapers reported that one of its name-boards and a labeled life-ring had been found, on shores a hundred and fifty miles apart.

Those artifacts have since disappeared into the fog and mist of history — but a vivid memento of this distinguished vessel passes soon across our auction block, for you, perhaps, to own.

An exceptional survivor of 19th-century maritime artistry. Join us at the upcoming auction—or schedule a private appointment to view this remarkable work in person.

History like this deserves more than admiration—it deserves conversation. If the story of Louis Gauvin, the Ivanhoe, and this extraordinary ceremonial powder horn has sparked your curiosity, we invite you to take the next step. Reach out to us to learn more about this remarkable piece, its provenance, and how it may find its next steward. Our specialists are always pleased to share insights, answer questions, and help you connect more deeply with the objects that carry history. Contact us today and become part of the story.

To gain early access to our entire scrimshaw collection and other highlights in our upcoming Winter Enchantment Auction, call 207-354-8141 or complete the form below to connect directly with a specialist. Subscribe to stay informed on future announcements and the release of the full catalog.